1137

Views & Citations137

Likes & Shares

This paper attempts to illuminate the path towards and into older age for those who are interested in grasping some of the realities of the journey. It is not the intention of the writer to create undue worry or concern surrounding the aging process but rather to solicit an interest in sharpening understanding, thinking and conversations about the nature of the road ahead. While each traveler will age in their own way, it is held that aging is more negotiable when the individual invests increasing interest in interpreting, reviewing and re-evaluating one’s life. Conversations of the right kind, and in sufficient depth relating to the aging experience may help to confront and resolve personal and existential challenges and issues, particularly when one has been assigned the label of ‘old person’. It is shown that intraversing the socio-economic-cultural landscape there will be differential insights, encounters and experiences with poverty and privilege including marginalization, disempowerment, inequality, citizenship, human rights and social justice. Perspectives on ageismwith its systematic stereotyping ispresented in order to provide a warning on how it can damage self-esteem and the health of its victims. Social integration and support are shown to provide a positive approach to the life journey in older age. The metaphor of the journey is utilized to demonstrate that the pathways traveled in early and mid-life influence the level of health and wellbeing in later life.

Keywords:Aging society, Compassionate ageism, Conspiracy of silence, Finite, Healthy life expectancy, Life chances,Life course, Self-disputation

INTRODUCTION

“I consider the old who have gone before us along a road which we must travel in our turn and it is good we should ask them of the nature of that road”-Socrates, The Republic

Travel of any kind involves elements of planning, scheduling and risk taking along with decisions and choices, and so it is also with the journey of life [1].Charting one’s life journey is context bound as well as culture bound and in combination both influence the aging experience.Featherstone and Wernick [2] in a portrayal of the acquired experiences and influences over the life journey argue “the aging body is never just a body subjected to the imperatives of cellular and organic decline, for as it moves through life it is continuously being inscribed and reinscribed with cultural meanings”(pp 2-3). It is not normal practice for younger generations to seriously ponder their old age and besides, this would entail contemplating their finitude and ultimate decline and eventual death. It would seem prima facie that there is a case for facilitating serious ongoing conversations on human aging whenwe consider that from the moment of our birth that the majority of us worldwide will progress through a life course, grow old and eventually die.Simone de Beauvoir[3] in her text ‘Old Age’provides a caveat for younger generations who more often than not embrace what she terms a ‘conspiracy of silence’leading to a failure to accept that “when we are young or in our prime we do not think of ourselves as already being in the dwelling place of our own future old age”(p 11). Further, de Beauvoir draws attention to an important yet poorly understood fact concerning the journey into older age “As a personal experience, old age is as much a women’s concern as a man’s-even more so, indeed, since women live longer” (p 101).

The avoidance of serious conversations on aging and old age might well be explained by our fear and dread of facing our own mortality [4] resulting in a less than determined quest tounderstand that “Every person who lives in an aging societyis a citizen of an aging society” (p S8] [5]. Palmer et al. [6] make the realistic but poorly understood point, that if we live long enough, then each of us individually will have to face the challenges of aging and “the challenges will raise existential matters that have been neither noticed nor processed during the younger years” (p 2).Moody [7] sees value in taking time to reflect in order to face up to the personal challenge of aging by symbolically looking at ourselves “in the mirror because aging is finally, just ourselves and not an “object” beyond ourselves” (p 238). We all have a stake in understanding the aging process, not only for ourselves but for our loved ones as well as humankind. Each individual from childhood, adolescence, young adulthood through to middle-age and older age is in the process of becoming, never complete, and somewhat indefinite in terms of self-image. Smith [8] nowarticulates the process well by first positioning the notion of ‘becoming’with change, meaning that with exit from each life stage the individual “knows that he (she) is no longer what he (she) was, and not yet what he (she) will be. He (she) is not quite one thing and not wholly something else” (p 15). This paper aims to foster conversations that are deep in content among and between those who are already older adults and those who are not prepared to fool themselves into believing or denying their own aging selves. At the same time, it is hoped that each respective reader will accept the challenge to undertake a measure of self-dialogue leading to “a deeper, more realistic awareness of the multifaceted nature of life’s final season” [9]. The practice of self- dialogue can solicit a form of self-disputation which in essence promotes emotional and passionate argument with the self on “matters pertaining to goals, values and life-style orientations. This form of self-argument provides insights that can help to challenge limiting perspectives on life and reality” (p 97) [10].

Perhaps the following reflection attributed to the warrior Karna in the Hindu Epic Mahabharata and extractedfrom Atul Gawande’s “Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End” might help to generate a heightened level of consciousness surrounding our finitude including the need to know something of the road ahead: I see it now-the world is swiftly passing.

CITIZENSHIP, HUMAN RIGHTS AND SOCIAL JUSTICE: A CURSORY GLANCE

Although it is not the intention in the present situation to delve deeply into the conceptual orientations relating to citizenship, human rights and social justice, they are introduced as a means of underscoring and positioning their respective and combined value in looking at aging and old age. It goes without saying that most aged care systems are designed to come first rather than focusing squarely on the needs of older individuals. Roberts [11]in recognition of the gravity of the challenges surrounding aging and old age states “As a society, we need to recognize that ageing has reached a new frontier that requires different tools to carve out a better future. The next decade of octogenarians and centenarians, for example, may require ‘a little bit of help’ of a type that has yet to be conceived” (p 52). Basok, Ican and Noonan[12]claim that social justice is not at present an attainable goal for some diverse groups and populations and put the view that social justice can be seen to be “an equitable distribution of fundamental resources and respect for human dignity and diversity, such that no minority group’s life interest and struggles are undermined and that forms of political interaction enable all groups to voice their concerns for change” (p 267). Citizenship is usually examined in the context of participation in a nation-state involving issues of identity, belonging, social relationships, social inclusion, equality and agency. However, the notion of national citizenship is now under constant challenge arising from the accelerated flows of diverse population groups across national borders involving large numbers of “labor migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers” (p 267) [12]. Aneesh and Wolover [13] highlight that large-scale population movements across the globe have implications for increased inequalities and infringements on human rights.

Attempts to lower health care costs has recently resulted in a move to utilize the concept of ‘participation’ as “a tool for defining a citizen’s identity” (p 86) [14]. The preceding trend is in danger of shifting the concept of citizenship in old age to the ‘slippery slope’. “Because notions of citizenship are narrowed down to a definition of active participation, some older adults might be excluded due to their physical restraints” (p 187) [14]. Social citizenship should not be confined solely to labor participation or to social and physical type activities but in accord with the following view point expressed by Knijn and Kremer [15] “we argue for a conceptualization of citizenship which acknowledges that every citizen will be a caregiver sometime in their life: all human beings were dependent on care when they were young and will need care when they are ill, handicapped, or frail and old. Care is thus not a women’s issue but a citizenship issue” (p. 332). Any discussions on inclusive citizenship should be mindful of any approaches that promote the idea that ‘social citizenship’ refers to rights and responsibilities in which the individual must be cognitively able to claim his/her rights and responsibilities [16]. In opposition to the preceding movement we have heard a host of voices advocating for a social citizenship model of dementia in which people suffering dementia related disorders are seen as active social agents [17-19]. It is hoped that future social policy and resource allocation will provide new and humanistic caring approaches to people with dementia that recognizes their personhood as well as empowering them as citizens.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) represents a watershed document released by the United Nations in 1948 aimed at recognizing and protecting the dignity, equality and inalienable rights of all people worldwide. Central to the proclamation of human rights is the call for universal protection of the most vulnerable members of society. In support of quality aged care in Australia the Australian Human Rights Commission in 2012 [20] launched a document entitled “Respect and Choice: A HumanRights Approach for Ageing and Health”with the statement “By adopting a human rights approach we are able to better understand how health services can be delivered in a manner that is non-discriminatory and promotes equality; ensures that services are available, accessible, appropriate and of good quality; and have adequate monitoring mechanisms and ensure government accountability” (p. 1). However, the issue of human rights for older people is still in need of serious attention and according to Tang and Lee [21]and Megret [22], there exists much work to move to an international convention on the rights of older people.Barrio et al. [23] make the unequivocal statement which would have no difficulty in aligning with the current understandings of human rights “Older people have the right to enjoy full citizenship and to actively participate in a comprehensive manner in society, claiming to be social subjects and rather than objects of attention and administration” (p 11). Kelly [24] provides a clear and unequivocal account on the right of older people to be aligned with citizenship status “Ageing should be viewed as part of the life course, and not as a condition apart from the rest of society. Older persons can be caretakers, as well as need to be cared for. They can be recipients of benefits such as pensions and health care, as well as contributors to the economy” (p. 34).

While the provision of quality-based health care for older people is a critically important citizenship issue there is also the societal obligation to deal with problems arising from “housing insecurity, food insecurity, or lack of ability to pay for needed care” (p S4) [5]. In light of the diversity and circumstances surrounding the health status of human beings, there exists, irrespective of age and nationality, strong ethical and moral grounds for countries worldwide along with established international health agencies to first acknowledge the social, economic and environmental determinants of health, and in so doing, action rigorous measures to develop, implement and evaluate policies and programs that permit equitable access to health care and related support services across all age groups. This means that without exception, that both young and old alike require within the context and spirit of human rights to be free from discrimination in terms of accessing health care support and services when and where the need arises. Cox and Pardasani [25] articulate the grounds for increased vulnerability among the aged “The physiological, social, and economic changes that commonly impact older adults and frequently contribute to dependency make them vulnerable to having their human rights violated” (p 98). The World Health Organisation [26]drawing upon the 2002 Toronto Declaration on Equity and Health adopted at the Second International Conference of the International Society for Equity in Health maintains: “Equity in health is a cornerstone of individual, community, societal and international well-being. Equity in health is built upon people having access to the resources, capacities and power they need to act upon the circumstances of their lives that determine their health”(p 3).

It would seem reasonable to argue that the notions of citizenship and human rights would on the face of their own broad conceptualizations offer complementary links with the overall notion of social justice. However, there remains the challenge to periodically examine the notions of citizenship and human rights with fresh thinking along with a genuine willingness to make changes and subsequent updates when deemed necessary [27,28]. In the end, the true measure of a society’s commitment to social justice in relation to caring for older people requiring residential and nursing care is how well it is able to demonstrate its level of attachment to humanitarian values and unwavering commitment to human rights as advocated by Ray [29]:

“A critical perspective in practice with older people would reasonably place a greater emphasis on human rights perspectives as a means to guide appropriate actions to challenge aged-based discrimination and to promote the commitment that older people with high support needs have the right to personhood and citizenship being upheld, supported and defended”(p 149).

AGEISM: A SOCIETAL BLIGHT

Historically and up to the present time many older people worldwide regardless of their cultural and ethnic background have suffered or are suffering from ageism, discrimination, prejudice, alienation, violence and abuse [31-36]. Megret [22] drawing upon the work of Johnson and Byetheway[37] provides a clear and succinct definition of ageism “as the view that people cease to be people, cease to be the same people or become people of a distinct and inferior kind, by virtue of having lived a specified number of years” (p 60). The renowned social gerontologist Robert Butler in his 1975 text “Why survive? Being Old in America” [38]introduced his insightful and scholarly portrayal on ageism. In essence, he introduced three major aspects of ageism that encompassed a) negative and pejorative attitudes towards older people including the attachment of such attitudes by older people to themselves b) discriminatory practices toward older people in employment and elsewhere throughout society and c) damaging stereotypes and practices deployed in institutional settings and social policies and programs [39]. In light of population aging worldwide there is an urgent need to understand and combat ageism due to resultant outcomes such as inequality, social exclusion, differential levels of abuse and lowered participation of older people in mainstream society [40,41] For the most part, there are two powerful narratives relating to aging and old age. The first concerns decline and deterioration with its focus on the ‘bio-medical model’ and its counterparts the ‘illness model’ and the ‘crises intervention model’ [42]. The second entails stories of progress, growth, development, active aging, successful aging along with aging-well [10,43,44]. Either way, unchallenged and overstated myths and stereotypes whether positive or negative surrounding aging and old age ignore the ambiguities, diversity and uniqueness accompanying the journey into older age [45]. Old age is really just another aspect of being alive and everybody does it differently biologically, psychologically and emotionally with differential impacts arising from the historical, socio-economic and cultural influences operating over the life course.

Notwithstanding the negative orientation towards aging and old age during antiquity there exists ample evidence from the 1930s and 1940s of the medical viewpoints that focused on the problems of old age and the impending crises resulting from population aging [46-48]. It is interesting to note the following commentary by the American psychologist Lillien Martin taken from her text “Salvaging OldAge” published in 1930 “When we have arrived at the place of looking at old age as a period of life rather than a bodily condition, we shall give it the intelligent and careful study that we have applied to other such periods, infancy, childhood, adolescence etc. i.e. as a period with its own struggles, its aspirations and accomplishments” (p 24). Martin was a strong advocate for adopting a professional approach to old age with a particular focus on promoting psychological research and intervention to help deal with the mental and cognitive abilities of older people and the overall “problem-oriented picture of aging” (p 44)[48].It might be claimed that in the early part of the twentieth century that some medical practitioners including psychologists and social workers were embracing either deliberately or unwittingly a form of whatMinkler[49] terms ‘compassionateageism’ which results from ‘advocacy’ efforts to gain visibility and subsequent resource support for the aged by using negative images and stereotypes of the aged as problematic, poor, frail, infirm, passive, demented and chronically-ill. There is of course the other side of the case where adaptation, resilience and growth represent a more realistic and positive approach to aging for the majority of older people. Aronson [50]provides an encouraging and balanced perspective that acknowledges the need to look beyond the medicalization of aging “Old age is partly defined by illness, but it is also normal, a natural part of life. If we want to understand and optimize it, we must look not only at medicine but into other realms of human thought and experience” (p 249). Higgs [51] claims that “it is ageism not biology that dominates the lives of older people” (p 121). Higgs argues for a more balanced understanding between health and aging resulting in a situation whereby “The stereotyping of old age as infirmity would be challenged as active older people become more visible in society” (p 122). Birren and Lanum[52] highlight an interesting response to a world facing increased life expectancy and entrenched negative attitudes that lead to ageist type behaviours “The fight against ageism has resulted in a set of counter-myths that show old people as capable of endless adaptability and happiness” (p 117). While an optimistic orientation to aging is preferable to an excessive and foreboding level of pessimism there remains the need to avoid unrealistic images of aging on both accounts. Why is it then, that we can have people recognizing intellectually that ageist attitudes and prejudicial behaviours towards the aged while unacceptable, are nevertheless, still perpetuated in a variety of shapes and forms throughout society? Mahon and Campbell [53] make the point that “recognizing something does not lead to acting differently. For that to happen, we need a deeper level of attention. One that allows people to step outside their traditional experience and truly feelbeyond the mind” (p 150).

Russell and Kendig [54] proffered the view that while it is possible to deconstruct and reconstruct our negative attitudes about aging and old age the challenge will forever remain a difficult task.Aronson [50] citing from the work of the psychologist Gordon Allport[R1] [58] in his text “The Nature of Prejudice” offers the following extract “People who are aware of, and ashamed of, their prejudices are well on the road to eliminating them” (p 69). Berlinger and Solomon [5] suggest that a global perspective should be adopted when examining aging and aging societies as this provides “A first step in getting this topic in view, and becoming accustomed to thinking of ourselves as citizens of aging societies, is to recognize widespread habits of language that disenfranchise older adults from the societies in which they live” (p S4).

A rethink about aging akin to the aforementioned notion will of course necessitate a change in the mindset of everybody, particularly key decision makers that include politicians, policy makers, health professionals, town planners, scholars and educators. All too frequently, we have accepted without serious critique the bifurcation of society into ‘us’ those who have yet to enter the landscape of old age with its complex mix of biological and existential challenges and ‘them’ the elderly who are generally held to be out of the mainstream of society, and for the most part, in need of care and support in a myriad of ways [55]. By failing torecognizeand accept aging as a natural part of life along with acquiescing to the damaging and disparaging stereotypes that marginalize older people we are partyto a) endorsing ageism and b) accepting and treating older people “as less interesting and worthy, we devalue part of their humanity, and forfeit some of our own” (p 229) [50]. Policy makers concerned with aging and old age might well heed the advice offered by Graycar [56]:

“In policy design, it is always important to distinguish a condition from a problem. Ageing is a condition and is not necessarily a problem. One adapts one’s lifestyle as one ages, and conditions change. However, when there is great poverty, ill health, and dependency, these conditions change into problems, and policy design comes into play. Understanding for whom ageing is a problem is fundamental”(p 64).

AGING: ENTERING A NEW AND UNIQUELY SIGNIFICANT STAGE OF LIFE EXPERIENCE

The German writer, artist and politician Goethe has been credited with writing “Age takes hold of us by surprise” (p 316) [3]. Rather than be surprised we should note the words of Hootan[57] “we’re going to have to get over our surprise, and our prejudices about ageing, if only for the most selfish of reasons: because we’re now more likely than ever before to get old ourselves” (p 25). In attempting to understand aging it must be accepted that biology is only part of the explanation. Aronson[50] drawing upon sound research argues “How and when we age, and how we experience that aging, also depends on our environment, coping mechanisms, health, behaviour, wealth, gender, geography, and luck” (p 176).Bass [59] contends aging should be examined within a social inequality and social justice framework whereby the impact of unequal life chances across the life course results in “people who live in miserable poverty next to others of the same age who enjoy flourishing abundance” (p 767). If for no other reason than ‘self-interest’ citizens residing in an aging society should indulge in “critical reflection on the structural-societal processes framing the life experience and status of older individuals” (p 1160) [60].The Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010 [61] presented in the Marmot Review entitled “Fair Society, Healthy Lives” reveals “The graded nature of the relationship between income and health is consistent with the fact that a person’s relative position on the social hierarchy is important for health” (p 76). Powell and Hendricks [62] add further insights on the shape of well-being and inequality that help to explain the growing gap between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ in relation to overall life chances with implications for health and wellbeing over the life course:

“Those living on the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder labor under the burden of the avoidable lifestyle diseases, hunger and related maladies, not to mention the myriad social risks. Those on the upper reaches ofthe same ladder garner disproportionate shares of the resources and are able to support comfortable lifestyles” (pp 3-4).

Notwithstanding that genetics, personal choices, attitudes, social position and health policies influence aging the situation in terms of so called ‘successful aging’ or ‘aging well’ is very much an outcome of “born into privilege, bred in safe neighbourhoods with access to healthy foods, able to lead lives absent from many of the stresses known to accelerate aging” (p 277)[50]. Calasanti and Zajicek [63] taking a socialist-feminist approach to aging argue a strong case for respecting the diversity of life experiences over the life course. Their perspective is still relevant for contemporary society by drawing our attention “to the ways gender, racial/ethnic and class relations interact in the lives of people as they age” (p 126) [63]. Strawbridge, Wallhagen and Cohen [64] indicate that the field of gerontology has many advocates opposed to labelling older people with disability or illness as being unsuccessful. Berlinger and Solomon [5] raise two significant ethically based questions that are pertinent to an ‘aging society’ “What would it mean to see ourselves as members of the aging society in which we live? What moral obligations are bound up with that identity? “(S 4). The preceding questions should be of interest and concern for younger and older citizens alike, particularly for those who are inclined towards resolving problems of injustice and human rights abuses.

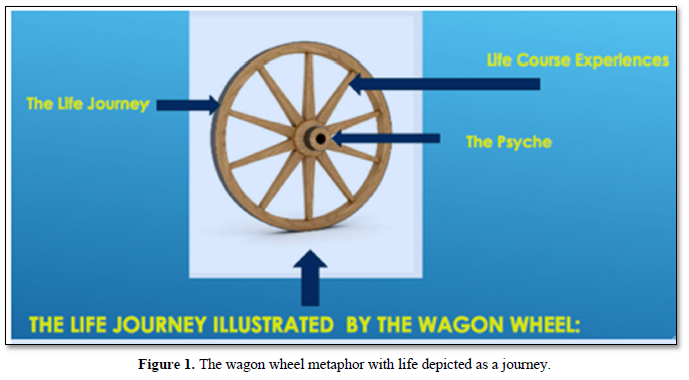

It must be appreciated that with advancing years, there will emerge a progressive sense of existential vulnerability based upon common knowledge emanating from medical science concerning the prevalence of frailty and ill- health in old age. However, this awareness should “not prevent the hope of belonging to a group of older adults who live well at a very high age. It becomes important to increase such possibilities by living a healthy way” (p3) [6]. To reach old age requires in part a genetic predisposition to do so, however, to achieve a good old age also requires an element of luck in combination with healthy lifestyle choices that include good social support networks [65-67]. Fratiglioni, Paillard-Brog and Winblad [67] in a study of lifestyle impact on dementia and Alzheimer’s disease provide evidence in support of adopting an active and socially integrated lifestyle in later life that comprises a balanced mix of the social, mental and physical. Knowledge and understandings impacting aging and old age can play a pivotal role in helping a person to negotiate the aging process [10]. La Russo [9] using the notion of ‘life as a journey’ proclaims “At every new stage of existence each of us is a new person entering a new region on the trail of life. We ask, at each entrance: What will it be like? Will it be even, uneven, rocky, smooth, filled with deserts, belle vistas, areas of cool shade, lakes, rivers, swamps, pits, mountains? And, deeper still are the burning questions: Can I endure? How will I fare?” (p viii). Figure 1 illustrates the wagon wheel metaphor with the movement of the wheel representing how the rim of the wheel traverses the life stages across the life course. The spokes represent the accumulation of life related experiences both positive and negative in which each traveller has to deal with loss and grief and a world in constant change. The hub of the wheel is synonymous with the psyche which relates to the conscious and unconscious aspects of the mind inclusive of emotions with implications for attitudes, decisions, choices, mental health and the construction of an individual’s evolving self and ego.

Conversations relating to aging and old age should take note of the advice offered to Erikson [68] in reference to his eight stages of human life development “If we let our observations indicate what could go wrong in each stage, we can also note what can go right” (p 58). This means that while there is factual knowledge of decline and morbidity along with loss and grief in older age there also exists opportunities, possibilities and potentials for growth, purpose and development in later life[1,44,69,70]. Walker [70] a strong advocate for active aging across the life course argues “while ageing is inevitable, it is also plastic. This means that it not only manifests itself in different ways but also that it can be modified by mitigating the various risk factors that drive it” (p 253).

Maddox [71] adds a further comment that supports the diversity surrounding the processes associated with aging and old age “So although in the long run we are all dead, we do not get there in identical ways biologically or socially” (p 61). Grundy [72] sees value in understanding aging and vulnerability and puts a case for promoting a healthy lifestyle across the life course inclusive of “the acquisition of coping skills, strong family and social ties, active interests, and savings and assets, will develop reserves and ensure that they are strong in later life” (p 105). Seedsman[73] offers a range of perspectives on living well in older age while emphasizing that there are a multitude of ways for doing so.Cohen [74] in “The Mature Mind”describes how the mind in later life solicits ‘inner pushes’ that facilitate positive opportunities for new forms of growth and development “We can, if we want to, learn, grow, love, and experience profound happiness in our later years” (p 182).

Willing [75] provides an important reminder when efforts are made to understand and learn from the unique stories of older people, in so far, that they may be accurate or only partly true they “may represent the experience yet omit the essence of it, which is the humanity of the person whose experience it was” (p 38). Work byCarteret [76] helps to elucidate the preceding viewpoint a little further “While each person has stories, tellingthem does not necessarily follow easily, it is determined by patterns of culture that have a strong hold on imagination. The tapestry metaphor provides a useful caution for researchers and interviewers to be mindful of cultural practices that can elide the knotty tangles of life and rich complexity for the sake of a coherent story” (p 34). Cole[77] provides a realistic perspective on aging that should be taken as neither supportive of a pessimistic or utopian orientation to later life:

“Aging like illness and death, reveals the most fundamental conflict of the human condition: the tension between infinite ambitions, dreams, and desires on the one hand, and vulnerable, limited, decaying physical existence on the other-between body and self. This paradox cannot be eradicated by the wonders of modern medicine or by positive attitudes toward growing old” (p 5).

HEALTHAND LIFE PRIORITIES: CONSIDERATIONS WORTH NOTING

Berlinger and Solomon [5] call for new ways of thinking about the concept of the ’good life’within the context of aging societies and what forces may hinder or advance wellbeing in later life.However, it must be said that those destined to live in the 21st century and beyond must be prepared to think and act in wholly new ways about personal health and wellbeing within the context of a life course perspective [70,78,79]. With the continuously growing older population worldwide there exists the urgent challenge for all societies large and small to promote good health practices among all older people. Indeed, it is now recognised and accepted that living into older age is no longer an exceptional happening but an expectation by increasing numbers of people [80]. As such, the pressures on all societies and their respective growing numbers of older people to confront the challenges of population aging and individual aging are unprecedented. Margaret Chan, a former Director General of the World Health Organisation identifies an important yet daunting challenge facing societies worldwide “Today, most people, even in the poorest countries, are living longer lives. But this is not enough. We need to ensure these extra years are healthy, meaningful and dignified. Achieving this will not just be good for older people, it will be good for society as a whole” (p 1) [81].

William Shakespeare in his play ‘The Tempest’coined the phrase “What’s past is prologue” taken in the present context to mean that the manner and circumstances relating to how life is lived in the early and middle stages is a precursor to health status in later life. Gupta[82] reminds us that “increased life expectancy is not yet translating into healthy life expectancy (p 309). Sarkisian, Hays and Mangione [83] in a study of 429 randomly selected community –residing adults aged 65-100 found that the majority of their study sample comprising both males and females “did not expect to achieve the model of successful aging in which high cognitive and physical functioning is maintained” (p 1837). Breda and Watts [84] make the point that while older adults are encouraged to adopt active and healthy lifestyles there nevertheless exists much variability in terms of the levels of uptake regarding physical activity and healthy lifestyles among the aged. Roberts [11] makes the salient point “The goal of a ‘good’ and productive long life is possible if there are appropriate interventions at the right time, if health inequalities are robustly addressed and if the individual is treated as a person with capabilities who is rooted in a community, not a bundle of problems and symptoms living an isolated existence” (p 14). Recognition must be given by families and health professionals that older people are in danger of becoming isolated and lonelier over time with implications for adverse effects on physical and mental health [85].

Resnick [86] reminds us that while access to healthcare represents an important social responsibility it must also be seen that “societies can promote health in many other ways, such as through sanitation, pollution control, food and drug safety, health education, disease surveillance, urban planning and occupational health” (p 444).Cutler-Riddick [87] highlights the fact that the health and wellbeing of older adults represents a measure of concern by nations worldwide as reflected in their respective economic and health related policies. Societies prepared to invest in the support of health and wellbeing of older citizens can expect to produce positive returns in terms of functional ability, community participation and economic contribution [80, 81].Muller [88] throws out a challenge in relation to low health literacy levels among the older population with negative consequences for health status and health outcomes. At the same time, personal lifestyle choices incorporated into a life course perspective also suggests that an element of personal responsibility is also an acceptable viewpoint for relegating a measure of ethical and moral accountability for personal health and wellbeing.Minkler[89] examined arguments regarding personal versus social responsibility for health and concluded that a more balanced approach was required for health promotion as the personal responsibility approach had limitations, and as such, required more thoughtful review and consideration. For Minkler [89] the task of health promotion must necessarily involve recognition of the social context impacting the individual’s health behavior, and as a consequence, she argued for a more realistic course of action “one that ensures the creation of healthy public policies and health promoting environments, within which individuals are better able to make choices conducive to health” (p 135).Spoel, Harris and Henwood [90] argue “what government says about the importance of healthy living is incompatible with what government does to support citizens’ abilities to eat healthily and live actively” (p 131).

Waldman-Levi, Bar-Haim Erez and Katz [91] provide a clue to understanding the level of commitment by older people to the pursuit of healthy living by suggesting that it may be due to “how each older adult interprets the aging process, thereby determining his or her overall quality of life”(p 5). Palmer et al. [6] add a further commentary on this perspective by stating “many older adults think of themselves in terms of health problems” (p 1). The preceding researchers also suggest that the term ‘misery research’ has been aligned with studies on aging and ill-health while emphasizing that for some older adults “Health problems are perceived as normal, and medical problems are accepted and tolerated without complete loss of the sense of well-being” (p 1). In the words of Lotes [92] “it is important to clarify that the demographic aging is, as a rule a sign of social development. Therefore, we do not consider aging a problem in itself. It will only be if, in association with it, we have high levels of chronic diseases and functional dependency” (p xvii). This preceding viewpoint brings to the fore the following complex question: Whose responsibility is it to promote the health and wellbeing of older people? Resnick [86] claims that “Responsibility for health should be a collaborative effort among individuals and the societies in which they live” (p 445). The preceding task, while complex would appear to be important in light of the increasing expenditures in healthcare, particularly in relation to the older population.Aronson [50] provides a telling commentary on the shortfalls common to medical care and focus in relation to aging and old age “Old age gets blamed for people’s declining health when our strictly medical approach to care leaves out or limits services and treatments for many of the conditions that make old age most challenging” (p 172).

Perhaps, it is time for the fields of gerontology and geriatric medicine to facilitate serious thinking and subsequent actions surrounding the controversial and ethical issues concerning the relation between aging, participation in healthy lifestyles and citizenship. In so doing, recognition must be given to a) the extent to which responsibility for personal health aligns with citizenship itself and b) the damaging potential arising from an all too limiting view of citizenship as entailing active participation in society[14]. Seedsman [10] argues that the ability to manage self-care along with maintaining a high level of self-esteem “is frequently the difference between being old yet active and being sick and frail” (p 68). Self-care based upon sound medical advice that incorporates a sensible regime of regular physical activity can facilitate habitual forms of healthy behaviour that can slow functional loss. Fontane [93] writing on the benefits of exercise in later life emphasizes the positive effect on biological functioning and “For older persons, decisions to exercise will promote good health, improve adaptation to the social environment, and assist adjustment to changing personal conditions, all contribute to aging well” (p 295). Any discussion on aging and personal responsibility for health must also consider issues surrounding self-neglecting behaviours involving cognitive, biomedical, nutritional, and psychiatric disorders.A cautionary note is in order, in so far, that there is a real danger of engaging in ‘blaming the victim’ or slinging hurtful and damaging innuendos against those who are not able for whatever reason(s) to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviours. At the same time, credence must be given to the fact that in some instances self-neglect stems “from a host of personal attitudes and behaviours that in reality are preventable or reversible”(p76)[10]. While the notion of personal responsibility can be viewed as having a persuasive appeal in public health campaigns there are also ethical and moral implications emanating from such communications [94]. It might be said that the concept of ‘due diligence’ should be applied to the medical fraternity in terms of the need to encourage patients, particularly those approaching older age and beyond, to adopt a disciplined approach to regular health checks and physical activity. At the same time, any attempt by the older person to: “maintain health cannot completely put away the thoughts of death as an upcoming factuality. This insight makes it urgent to not postpone all things that feel important to do while there is still time to do them” (p 4) [6]. Our finiteness is made unequivocally clear byDohmen[95] “everything in our life is finite: our youth, parenthood, love, friendship, knowledge, meetings, results, and even fame” (p.48).

CONCLUSION

The longevity revolution is impacting all societies worldwide, and as such, it will be incumbent upon the citizenry in each aging society “to build a better more egalitarian society capable of recognizing the value of each individual regardless of their age and social, cultural or racial background” (p 11) [23]. In so doing, it will be necessary to ensure that conversations on aging and old age are ever mindful of diversity and heterogeneity as well inclusiveness when undertaking the challenging task of designing and implementing policies that affect older people, either directly or indirectly. Achenbaum [96] provides an interesting perspective that is perhaps not far from explaining the failure of some gerontologists and health professionals who “rarely get inside the experiences of ageing” (p 24). The preceding viewpoint is elaborated further by McNamara [97]:

“Scientific meanings of aging are separated from and elevated above experiential or existential understandings. This has vital implications for any dealings with aging persons. Not to prize their experience and the process of understanding and giving meaning to this part of their journey is radically undermining of their uniqueness, individuality and dignity” (p 66).

Moody [7] reminds us in a telling and sobering manner that we live in “a shared human world where actions have consequences and where our full humanity and sense of responsibility are engaged” (p 237). Citizenship entails responsibilities, obligations as well as rights, and when it is recognized that being a citizen constitutes membership of a social system, then surely collective efforts should be focused upon how best to design and implement humanepublic policies across the entire life course. Aronson [50] draws our attention to the inequality and injustice surrounding older person care “Wealth and personal connections should not be required for older adults and their families to get needed care” (p 150). Surely it makes sense to engage in serious conversations between the generations in order to ensure that life is valued at all stages of the life course. Only through the undertaking of genuine negotiations between the generations can older people be provided the necessary support and opportunity to actively participate in society including provision of health care services that are available, accessible, and affordable in times of need. For Maddox [71]:“These negotiations are primarily political, not a scientific exercise. The future of aging, therefore, depends substantially on the achievement of political consensus, the mobilization of political intentions and will, and the political ingenuity to shape the future of aging” (p 66).

In the end, it is worth noting the view expressed by Mahatma Gandhi “The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members” (p 279) [98]. At the same time, a society claiming to be committed to social justice and human rights must be prepared to be judged to the extent that there exists a genuine recognition and acceptance that life in others matters significantly [99,100]. In terms of elder care there exists an urgent need to foster a sense of humaneness whereby there is recognition and action to find the right balance between the application of medical science and technology with kindness and compassion [101, 98, 50].While recognizing the advances in medical science and related technologies there is much to be said for improving human health and wellbeing through “justice in policy and kindness of attitude” (p 93) [50].Bertman [102] in a commentary on modern medicine and technological advances coupled with stresses, distractions and time constraints on physicians argues “the potentially healing bond between doctor and patient is being frayed and the quality of care consequently degraded” (p 57). Arai et al. [103] in a review of challenges facing the health and wellbeing of older Japanese citizens argue a case for advancing the fields of gerontology and geriatrics which also has relevance for countries worldwide:

“Furthermore, along with a need for multidisciplinary care to support geriatric medicine, the development of a comprehensive education system for aged-care professionals is awaited. Thus, we should now recognize the importance of gerontology and geriatrics, and a reform of medical-care services should be made in order to cope with the coming aged society” (p 16).

The litmus test as it applies to the treatment of older people should be the extent to which sufficient care, support and resource allocation is available and applied in a manner that reflects Albert Schweitzer’s ethical stance that holds firmly to a ‘reverence for life’ [104,105]. The design of health care systems for older people should be such that the focus is on the provision of a person-centred approach that a) respects the older person as a unique individual entitled to quality based care at all times and b) puts the older person and their family at the core of all decision making in relation to the provision of care [106]. Aged care systems found to be at odds with ‘fit for purpose’ should be made accountable to do so, or face sanctions of the most severe kind. It is hoped that the facilitation of conversations of the right kind, in the right place, with the right people, and at the right time, will lead to the development of more just and humane policies and programmes that support the diverse needs of people in later life. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised ethical and moral dilemmas associated with the development and focus of testing regimes, clinical care and attention across age groups.Lithander et al. [107] identified a major deficit among some clinicians in terms of being familiar with the field of geriatric medicine and clinical treatment associated with CORVID-19. The same researchers emphasized that it is “imperative that research is proactively inclusive of older people so as to optimize prevention, treatment and rehabilitation strategies in this at-risk group” (p 11). It will be essential that post pandemic reviews and evaluations examine the extent to which the development of clinical protocols for treating older people were deemed to be less important than was the case for younger adults and children. This examination is important to ensure that ageist type attitudes did not contribute to any shortfall in treatments for older people who were at greater risk of hospitalization and death than any other population group [108]. The challenge facing societies worldwide in terms of demonstrating empathetic recognition and compassion for older people in need of care and support is clearly articulated in the following statement taken from a report by the President’s Council on Bioethics (US) (2005):Taking Care: Ethical Caregiving in Our aging Society [79]:

“Of course, every society is both imperfect and limited: it never treats everyone as well or as fairly as it should, and it must balance many civic goods and obligations. But in no small measure, the kind of society we are will be measured in the years ahead by how well (or how poorly) we care for those elderly persons who cannot care for themselves; by whether we support the caregivers who devote themselves to this noble task; and by whether we sustain a social world in which people age and die in humanly fitting ways always cared for until the end, never abandoned in their days of greatest need” (p 97).

1. Kenyon GM (1991) Homo viator: Metaphors of aging, authenticity, and meaning. In Kenyon GM, Birren JE, Schroots JJF (Eds.), Metaphors of aging in science and the humanities. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

2. Featherstone M, Wernick A (1995) Introduction in Featherstone M, Wernick A (Eds) Images of aging: Cultural representations of later life. New York: Routledge.

3. Beauvoir SD (1977) Old age Middlesex UK. Penguin Books.

4. Abramson CM, Portacolone E (2018) What is new with old? What old age teaches us about inequality and stratification Sociol Compass 11: e12450.

5. Berlinger N, Solomon M (2018) Becoming good citizens of aging societies. Hastings Centre Report, 48: 1-9.

6. Palmer L, Nystrom M, Carlsson G, Gillsjo C, Eriksson I, et al. (2019) The meaning of growing old: A life world hermeneutic study on existential matters during the third age of life. Healthy Aging Res 8: 1-7.

7. Moody HR (1989) Gerontology with a human face. In l. E. Thomas (Ed.), Research on adulthood and aging: The human science approach. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

8. Smith AG (1970) To nurture humaneness. Washington, DC: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, NEA.

9. Russo DL (1994) Foreword. In T. Seedsman, Ageing is negotiable: A prospectus for vital living in the third age. Melbourne: Working Effectively Inc.

10. Seedsman T (1994) Ageing is negotiable: A prospectus for vital living in the third age. Melbourne: Employ Working Effectively Inc.

11. Roberts Y (2012) One hundred not out: Resilience and active ageing. London: The Young Foundation.

12. Basok T, Ilcan S, Noonan J (2006) Citizenship, human rights and social justice. CitizenshStudi 10: 267-273.

13. Aneesh A, Wolover DJ (2017) Citizenship and inequality in a global age. Sociology Compass 11: 1-9.

14. Hees SV, Horstman K, Jansen M, Ruward D (2015) Conflicting notions of citizenship in old age: An analysis of an activation practice. J Aging Stud 35: 178-189.

15. Knijn T, Kremer M (1997) Gender and the caring dimension of welfare states: Toward inclusive citizenship. Soc Politics 4: 328-361.

16. Bruens MT (2014) Ageing, meaning and social structure: Connecting critical and humanistic gerontology. Bristol, UK: Polity Press.

17. Koppeleman ER (2002) Dementia and dignity: Towards a new method of surrogate decision making. J Med Phil 27: 65-85.

18. Baldwin C (2008) Narrative (,) citizenship and dementia: The personal and the political. J Aging Stud 22: 222-228.

19. Bartlett R, Connor DO (2010) Broadening the dementia debate: Towards social citizenship. Bristol: The Policy Press.

20. Australian Human Rights Commission (2012) Respect and choice: A human rights approach for ageing and health. Sydney, NSW: Human Rights Commission.

21. Tang KL, Lee JJ (2005) Global justice for older people. The case for an international convention on the rights of older people. Br J Soc Work 36: 1135-1150.

22. Megret F (2011) The human rights of older persons: A growing challenge. Hum Rights Law Rev 11: 37-66.

23. Barrio ED, Marsillas S, Buffel T, Smetcoren, An-S, et al. (2018) From active aging to active citizenship: The role of (age) friendliness. Soc Sci 7: 134.

24. Kelly PL (2006) Integration and participation of older persons in development. A paper authored by Peggy L. Kelly, Social Affairs Officer, Programme on Ageing, Division for Social Policy and Development, Department of Economic and Social Affairs-United Nations Secretariat.

25. Cox C, Pardasani M (2017) Aging and Human Rights: A Rights-Based Approach to Social Work with Older Adults. J Hum Rights Soc Work 2: 98-106.

26. World Health Organisation (2008) Healthy ageing profiles: Guidance for producing local health profiles of older people. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

27. Dodds S (2005) Gender, ageing and injustice: Social and political contexts of bioethics. J Med Ethics 31: 295-298.

28. Grenier AM, Guberman N (2009) Creating and sustaining disadvantage: The relevance of a social exclusion framework. Health Soc Care Commun 17: 116-124.

29. Ray M (2014) Ageing, meaning and social structure: Connecting critical and humanistic gerontology. Bristol, UK: Polity Press.

30. Baer B, Bhushan A, Taleb HA, Vasquez J, Thomas R (2016) The right to health of older people. Gerontologist 56: 206-217.

31. Pillemer K, Finkelhor D (1988) ‘The prevalence of elder abuse, a random survey. The Gerontologist 28: 51-57.

32. James M (1994) Abuse and neglect of older people. Fam Matters 37: 94-97.

33. Feldman S (1999) ‘Please don’t call me dear’ Older women’s narratives of health care. NursInq 6: 269-276.

34. Angus J, Reeve P (2006) Ageism: A threat to “ageing well” in the 21st century. J Appl Gerontol 25: 137-152.

35. Australian Human Rights Commission (2010) Age discrimination - exposing the hidden barriers for mature age workers. Sydney, NSW: Public Affairs/ Australian Human Rights Commission.

36. Pillemer K, Bumes D, Riffin C, Lachs MS (2016) Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Gerontology 56: 194-205.

37. Johnson J, Bytheway B (1993) Ageism: Concept and definition. In Johnson J, Slater R (Eds), Ageing and later life. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

38. Butler RN (1975) Why survive? Being old in America. New York: Harper and Row.

39. Malta S, Doyle C (2016) Butler’s three constructs of ageism in Australasian J Ageing (Virtual Issue Editorial). Australian J Ageing 35: 232-235.

40. Butler RN (1969) Age-ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist 9: 243-246.

41. Abrams D, Swift HJ, Lamont RA, Drury L (2015) The barriers to and enablers of positive attitudes to ageing and older people, at the societal and individual level. Technical report. Kent, UK: Government Office for Science.

42. Davidson W (1991) Metaphors of health and aging: Geriatrics as metaphor. In Kenyon GM, Birren JE, Schroots JJF(Eds.) Metaphors of aging in science and the humanities. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

43. Johnson TF (1995) Aging well in contemporary society. Am Behav Sci 39: 120-130.

44. Lupien SJ, Wan N (2004) Successful ageing: From cell to self. Royal Soc 359: 1413-1426.

45. Dionigi RA (2015) Stereotypes of aging: Their effect on the health of older adults. J Geriatr 2015: 9.

46. Martin LJ, Gruchy CD (1930) Salvaging old age. New York: Macmillan Company.

47. Zeman FD (1944) The medical and social problems of old age: A critical bibliography for nurses and social workers. Am J Nurs 44: 1046-1048.

48. Hirshbein LD (2002) The senile mind: Psychology and old age in the 1930s and 1940s. J Hist Behav Sci 38: 43-56.

49. Minkler M (2018) Readings in the political economy of aging. New York: Routledge.

50. Aronson L (2019) Elderhood: Redefining aging, transforming medicine, reimagining life. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

51. Higgs P (1997) Critical approaches to ageing and later life. Buckingham, London: Open University Press.

52. Birren JE, Lanum JC (1991) Metaphors of aging in science and the humanities. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

53. Mahon EM, Campbell P (2010) Excerpts from the introduction to “Rediscovering the lost body: Connection within Christian spirituality”. The Folio 22: 147-154.

54. Russell C, Kendig H (1999) Social policy and research for older citizens. Australas J Ageing 18: 44-49.

55. Cox KS (2017) Guest Editorial: Ageism: We are our own worst enemy. Psychogeriatri 29: 1-8.

56. Graycar A (2018) Policy design for an ageing population. Policy Des Pract 1: 63-64.

57. Hootan A (2019) Now and forever The Age. Good Weekend 24-26.

58. Allport G (1952) The nature of prejudice. Boston: Beacon Press.

59. Baas J (2017) Aging, social inequality, and social justice. Innov Aging 1: 767-768.

60. Laceulle H (2014) Ageing, meaning and social structure: Connecting critical and humanistic gerontology. Chicago, IL: Polity Press, pp: 97-118.

61. Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010 (2010) Fair society, healthier lives: The Marmot review. Available online at: http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review-full-report.pdf

62. Powell J, Hendricks J (2009) The welfare state in post-industrial society: A global perspective. Dordrect: Springer.

63. Calasanti TM, Zajicek AM (1993) A socialist-feminist approach to aging: Embracing diversity. J Aging Stud 7: 117-131.

64. Strawbridge W, Wallhagen M, Cohen R (2002). Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 42: 727-733.

65. Atallah N, Adjibade M, Lelong H, Hercberg S, Galan P, et al. (2018) How healthy lifestyle factors at midlife relate to healthy aging. Nutrients 10: 854.

66. Bosnes I, Nordahl HM, Stordal E, Bosnes O, Myklebust TÅ, et al. (2019) Lifestyle predictors of successful aging: A 20-year prospective HUNT study. PLos ONE 14: e0219200.

67. Fratiglioni L, Borg SP, Winblad B (2004) An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. The Lancet 3: 343-353.

68. Erikson E (1979) Reflections on Dr, Borg’s life cycle. In Van Tassel D (Ed), Aging, death, and the completion of being (pp. 29-67). University of Pennsylvania Press

69. Kruse A, Schmitt E (2012) Generativity as a route to active ageing. CurrGerontolGeriatr Res 2012: 9.

70. Walker A (2017) Why the UK needs a social policy on ageing. J Soc Policy 47: 253-273.

71. Maddox GL (1992) Aging and well-being. In Cutler NE, Gregg DW, Powell Lawton M (Eds), Aging, money, and life satisfaction: Aspects of financial gerontology. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

72. Grundy E (2006) Ageing and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Ageing Soc 26: 105-134.

73. Seedsman T (2020) The art of living well and the gaining of practical wisdom in later life: Perspectives for undertaking future work in the intergenerational field. J IntergenerRelat.

74. Cohen GD (2005) The mature mind: The positive power of the aging brain. New York: Basic Books.

75. Willing J (1981) The reality of retirement: The inner experience of becoming a retired person. New York: William Morrow.

76. Carteret PD (2009) Life is a tapestry: A cautionary metaphor. CurrNarrat 1: 23-34.

77. Cole T (1986) What does it mean to grow old? Reflections from the humanities. Durham: Duke University Press.

78. Walker A (2009) The emergence and application of active ageing in Europe. J Aging Soc Policy 21: 75-93.

79. President’s Council on Bioethics (US). (2005) Taking care: Ethical care giving in our aging society. Washington, D.C: President’s Council on Bioethics. Accessed on: November 7, 2006. Available online at: http://www.bioethics.gov/reports/taking_care/taking_care.pdf

80. Crampton A (2011) Population aging and social work practice with older adults: Demographic and policy challenges. Int Social Work 54: 313-329.

81. World Health Organisation (2017) Developing an ethical framework for healthy ageing (Report of a WHO meeting Tubingen, Germany, 18 March). Geneva: World Health Organisation.

82. Gupta N (2016) Population ageing: Health and social care of elderly persons. ArthaVijnana LV 111: 399-406.

83. Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, Mangione CM (2002) Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 50: 1837-1843.

84. Breda AI, Watts AS (2017) Expectations regarding aging, physical activity and physical function in older adults. GerontolGeriatr Med 3: 1-8.

85. Pate A (2014) Social isolation: Its impact on the mental health and wellbeing of older Victorians (COTA Working Paper No.1): Melbourne: Council on the Ageing Victoria.

86. Resnick DB (2007) Responsibility for health: Personal, social and environmental. J Med Ethics 33: 444-445.

87. Riddick CC (2016) Ageing, physical activity, recreation and wellbeing, Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

88. Muller E (2013) Health literacy challenges in the aging population. Nursing Forum 48: 248-255.

89. Minkler M (1999) Personal responsibility for health? A Review of the arguments and the evidence at century’s end. Heal Edu Behav 26: 121-140.

90. Spoel P, Harris R, Henwood F (2014) Rhetorics of health citizenship: Exploring vernacular critiques of government’s role in supporting healthy living. J Med Hum 35: 131-147.

91. Waldman LA, Bar HEA, Katz N (2015) Health aging is reflected in well-being, participation, playfulness, and cognitive-emotional functioning. Health Aging Res 4: 8.

92. Lotes M (2020) Handbook of research on health systems and organizations for an aging society. Hersley PA: IGI Global.

93. Fontane PE (1996) Exercise, fitness and feeling well. Am Behav Sci 39: 288-305.

94. Guttman N, Ressler WH (2001) On being responsible: Ethical Issues in appeals to personal responsibility in health campaigns. J Health Commun 6: 117-136.

95. Dohmen J (2014) Ageing, meaning and social structure: Connecting critical and humanistic gerontology. Bristol, UK: Polity Press.

96. Achenbaum, W. A. (1997). Critical gerontology: In A. Jamieson, S. Harper, & C. Victor (Eds.), Critical approaches to ageing in later life. (pp 6-22). Buckingham: Open University Press.

97. McNamaraLJM (1997) Just health care for aged Australians: A Roman Catholic perspective. Doctoral dissertation. Adelaide University, Department of Health, Adelaide, South Australia.

98. Watson C (2018) The language of kindness: A nurse’s story. London: Vintage.

99. Jopp D, Rott C, Oswald F (2008) Valuation of life in old and very old age: The role of sociodemographic, social, and health resources for positive adaptation. Gerontologist 48: 646-658.

100. Singer I (1992) Meaning in life: The creation of value. New York: The Free Press.

101. Gawande A (2015) Being mortal: Illness, medicine, and what matters in the end. London: Welcome Collection.

102.Bertman S (2017) Pursuing humanistic medicine in a technological age. J Patient Exp 4: 57-60.

103. Arai H, Ouchi Y, Yokode M, Ito H, Uematsu, et al. (2012) Toward the realization of a better aged society: Messages from gerontology and geriatrics. GeriatrGerontol Int 12: 16-22.

104.Globokar R (2015) The ethics of Albert Schweitzer as an inspiration for global ethics. Globalization and Global Justice: 52nd SocietasEthica Annual Conference. Linkoping, Sweden.

105.Pawlas A (2015) Notes to Albert Schweitzer, his concept of’ “reverence for life” and the fifth commandment. J Stud Soc Sci 11: 196-214.

106.Boggatz T (2020) Quality of life and person-cantered care for older adults. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

107.Lithander F, Neumann S, Tenison E, Lloyd K, Welsh T, et al. (2020) COVID-19 in older people: A rapid clinical review. Age Ageing 1-15.

108. Fraser S, Lagacé M, Bangue B, Ndeye N, Guyot J (2020) Ageism and COVID-19: What does our society’s response say about us? Age Ageing afaa 097.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

- Archive of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Medicine (ISSN:2640-2297)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- BioMed Research Journal (ISSN:2578-8892)

- Chemotherapy Research Journal (ISSN:2642-0236)

- International Journal of Medical and Clinical Imaging (ISSN:2573-1084)